More Information

Submitted: December 12, 2025 | Approved: December 26, 2025 | Published: December 29, 2025

How to cite this article: Gonzalo GM, De la Parte M, Roberto P, Ignacio MF, Paula B, Tania L, et al. Usefulness of Echocardiogram to Predict NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/mL. J Cardiol Cardiovasc Med. 2025; 10(6): 141-146. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.jccm.1001222

DOI: 10.29328/journal.jccm.1001222

Copyright license: © 2025 Gonzalo GM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Heart failure; NT-proBNP; Echocardiography; Cardiac congestion; Diastolic dysfunction; Predictive diagnostic model

Abbreviations: LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LA: Left Atrium; LVH: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; TAPSE: Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion; IVC: Inferior Cava Vena

Usefulness of Echocardiogram to Predict NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/mL

Guzzo-Merello Gonzalo1*, De la Parte Maria2, Picano Roberto3, Mahillo-Fernandez Ignacio4, Beltran Paula1, Luque Tania1 and Navarro Felipe1

1Department of Cardiology, General Villalba University Hospital, 28400 Madrid, Spain

2Department of Pediatrics and Cardiology, General Villalba University Hospital, 28400 Madrid, Spain

3Alfonso X el Sabio University, 28691 Madrid, Spain

4Biostatistics and Epidemiology Unit, IIS-Fundación Jiménez Díaz, 28040 Madrid, Spain

*Address for Correspondence: Guzzo-Merello Gonzalo, MD. PhD., Department of Cardiology, General Villalba University Hospital, 28400 Madrid, Spain, Email: [email protected]

Introduction and objectives: Although elevated natriuretic peptide levels form part of the universal definition of heart failure, values of echocardiographic parameters indicating congestion have not yet been defined. Our research aims to demonstrate the correlation between different echocardiographic parameters and NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/mL, the diagnostic threshold for heart failure in decompensated and hospitalized patients.

Methods: We performed a retrospective observational analysis of echocardiographic parameters and NT-proBNP levels from patients admitted to the cardiology inpatient unit of a tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain, with a suspected diagnosis of decompensated heart failure during 18 months.

Results: A total of 134 patients (68 female) were included. LV thickness, E/E’ lat, E/E’ med, E/E’ average, S-wave, E-wave, and IVC diameter were significantly associated with NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/ml. In contrast, LVEF, A-wave, and TAPSE were negatively correlated with NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/ml. E/E’ ratio >15 was found to be significantly related to NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml (p = 0.007), with a positive predictive value of 95%. The model with the highest predictive power for NT-proBNP levels of ≥300 pg/ml included LA diameter, A1, E/E’ mean, S-wave, LV thickness, and LVEF ((AUC 0.88 (0.81 – 0.94)).

Conclusion: Our research presents an accurate model that uses echocardiographic parameters to predict NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml, a diagnostic criterion for heart failure. Strong predictors of NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml included LA diameter, A-wave, E/E’ mean, S-wave, LV thickness, and LVEF. Our research defines echocardiographic parameters suggestive of cardiogenic pulmonary or systemic congestion that apply to the complete phenotypical spectrum of heart failure.

Heart failure is a common clinical syndrome affecting approximately 1% - 2% of the adult population in developed countries, with prevalence rising sharply with age. Global analyses estimate that more than 60 million people worldwide live with heart failure, reflecting its increasing burden on health systems.

As heart failure is a clinical syndrome with a broad range of underlying aetiologies and pathophysiology, definitions in the literature vary [1]. To overcome heterogeneities, a universal definition of heart failure has recently been proposed [2]. To meet diagnostic criteria, patients must present symptoms and/or signs of heart failure caused by a structural or functional cardiac abnormality. These findings must be corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels or objective evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary or systemic congestion [2].

Although elevated natriuretic peptide levels (NT-proBNP ≥ 300 pg/mL or BNP ≥ 100 pg/mL) have been established as definitive for confirming the diagnosis of heart failure, the values of echocardiographic parameters indicating congestion have not yet been defined [2,3]. While several echocardiographic parameters such as the E-wave deceleration time, the E/A ratio, and the E/E’ ratio have been correlated to increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and elevated PCP [4-6], to the best of our knowledge no studies have focused on the relationship between different echocardiographic parameters and natriuretic peptide levels in the context of the proposed universal definition of heart failure.

Our research aims to demonstrate the correlation between different echocardiographic parameters and NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/mL, which is the diagnostic threshold for heart failure in decompensated and hospitalized patients [2,4,7].

Study population

We performed a retrospective observational analysis including patients admitted to the cardiology inpatient unit or the emergency department of the General Villalba University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) with a suspected diagnosis of decompensated heart failure from January 1st, 2018, to December 31st, 2022. Patients were included if NT-proBNP levels and echocardiography had been performed within the same 24-hour interval during admission. Patients with severe mitral valve disease or presenting a prosthetic valve were excluded.

Data were extracted manually from the hospital’s electronic health record database. Variables included demographic and clinical characteristics, NTproBNP levels, and echocardiographic variables including LVEF (left ventricular ejection fraction), the presence of LVH (left ventricular hypertrophy), LA (left atrial) diameter, E-wave and A-wave velocities, E/E’ lat, E/E’ med, E/E’ ratio, S-wave, TAPSE, and IVC (inferior vena cava) diameter.

NT-proBNP analysis and echocardiography

NT-proBNP levels were measured using the Elecsys® proBNPII ECLIA electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostics, Rotkreuz). Standard echocardiographic images were obtained using Philips HD15 ultrasound machines, using the biplane, M-mode, Pulsed Wave (PW) Doppler, and Tissue Doppler modalities. Echocardiograms were performed by 2 members of the cardiac ultrasound team with more than 20 years of experience.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables describing the study population were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables, and median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normal variables. Qualitative variables were described as frequencies and percentages. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to analyze the relationship between NT-proBNP levels and other quantitative variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to study the relationship between NT-proBNP levels and qualitative variables.

After analysis of NT-proBNP as a continuous variable, we compared patients with NT-proBNP levels <300 pg/ml and ≥300 pg/mL. Quantitative normally distributed data were compared using the Student’s T-test. Qualitative data were compared using the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test. Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Logistic regression analysis was performed using a forward stepwise approach. First, variables were included and eliminated according to p-values. Then, different combinations of variables were tested until the best model. Patients with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation were excluded from logistic regression analysis due to missing data for A wave values. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 29.0.

Approval was obtained from the Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital Ethics Board for this study (number TFG047-23_HGV). Research was carried out according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study included a total of 134 patients, of whom 68 were female. Participants’ average age was 72.7 ± 13.3 years. The main characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Regarding clinical characteristics, patients’ average glomerular filtrate was 70.2 ± 22.7 mL/min/m2.

| Table 1: Clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of the study population. | |

| Number | 134 |

| Age | 72.7 ± 13.3 |

| Female sex | 68 (50.74%) |

| GF (ml/min/m2) | 70.2 ± 22.7 |

| Hypertension | 96 (73.3%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (32.8%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 51 (38.9%) |

| Underlying cardiopathy | 84 (64.1%) |

| Chronic renal disease | 35 (26.5%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 43 (32.6%) |

| BMI > 25 | 31 (23.5%) |

| NT-proBNP | 838 (170 - 2652) |

| Echocardiographic measurements | |

| LVEF (%) | 56.8 ± 14.8 |

| LVH (mm) | 9.46 ± 1.83 |

| LA (mm) | 44.0 ± 6.97 |

| S wave (cm/s) | 8.16 ± 2.73 |

| E wave (cm/s) | 0.95 ± 0.27 |

| A wave (cm/s) | 0.62 ± 0.47 |

| E/E´lat | 10.7 ± 4.49 |

| E/E´med | 14.1 ± 5.74 |

| E/E’ average | 12.3 ± 4.90 |

| TAPSE(mm) | 18.8 ± 3.97 |

| RV S wave (mm) | 12.6 ± 2.96 |

| IVC (mm) | 16.7 ± 3.96 |

| GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; BMI: Body Mass Index; LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVH: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; LA: Left Atrium; TAPSE: Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion; RV: Right Ventricle; IVC: Inferior Vena Cava. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed variables and median [interquartile range] for non-normally distributed variables. | |

The most common comorbidities present in our sample population were hypertension (73%), dyslipidemia (39%), atrial fibrillation (33%), diabetes mellitus (32.8%), chronic renal disease (26.5%), and a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25 (23.5%). Average NT-proBNP level was 838pg/ml (170-2652). Echocardiographic parameters for our study population included an average LVEF of 56.8% ± 14.8%, a mean left ventricle thickness of 9.46 mm ± 1.83 mm, and an average LA diameter of 44.0 ± 6.97 mm.

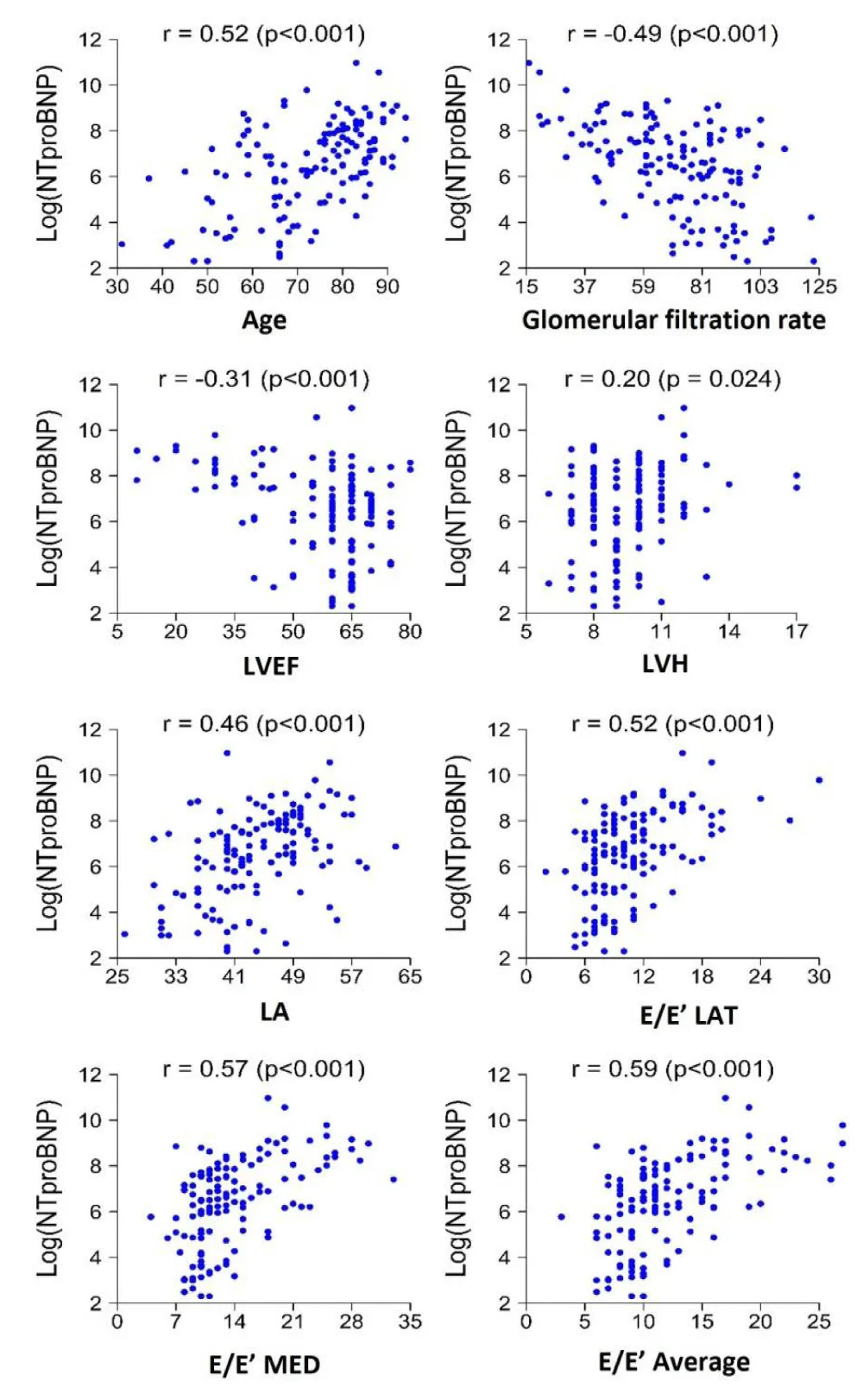

Results of the analysis of NT-proBNP as a continuous variable and its association with echocardiographic variables are presented in Table 2. A positive association was observed between NT-proBNP levels and previous diagnoses of hypertension (p < 0.001), preexisting cardiopathy (p < 0.001), chronic renal disease (p = 0.001), and atrial fibrillation (p < 0.001). Echocardiographic parameters found to be significantly correlated to NT-proBNP levels included LVH

| Table 2: Univariable correlations of echocardiographic parameters with log NT-proBNP levels. | ||

| Spearman’s correlation coefficient (Ρ) | p | |

| LVEF | -0.31 | <0.001 |

| LVH | 0.20 | 0.024 |

| LA | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| E/E’ lat | 0.52 | <0.001 |

| E/E’ med | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| E/E’ average | 0.59 | <0.001 |

| S wave | -0.54 | <0.001 |

| E wave | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Awave | -0.44 | <0.001 |

| TAPSE | -0.40 | <0.001 |

| RV S wave | -0.27 | 0.003 |

| IVC | 0.46 | <0.001 |

| LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVH: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; LA: Left Atrium; TAPSE: Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion; RV: Right Ventricle; IVC: Inferior Vena Cava. | ||

(R = 0.2, p = 0.024), LA (R = 0.46, p < 0.001), E/E’ lat (R = 0.52, p < 0.001), E/E’med (R = 0.57, p < 0.001), E/E’ average (R = 0.59, p < 0.001), and E-wave (R = 0.45, p < 0.001) (Figure 1). On the other hand, LVEF, A-wave, TAPSE, and S’-wave values were found to be negatively correlated with NT-proBNP levels, with R - values of -0.31, -0.44, -0.40, and -0.27 (p < 0.001).

Figure 1: Plot demonstrating the correlation of echocardiographic parameters with NT-proBNP levels. LVEF, left ventricular eyection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LA, left atrium.

Of the 134 patients, 95 (71.96%) had NT-proBNP levels of ≥300 pg/ml, the diagnostic threshold for hospitalized patients with heart failure or those with decompensated heart failure. Patients with NT-proBNP levels of ≥300 pg/ml presented significantly higher rates of comorbidities, including hypertension, previous cardiopathy, and chronic renal disease. Regarding echocardiographic parameters and their relationship to NT-proBNP levels, LV thickness, E/E’ lat, E/E’ med, E/E’ average, S-wave, E-wave and IVC diameter were significantly associated with NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/ml. In contrast, LVEF, A-wave and TAPSE were negatively correlated with NT-proBNP levels ≥300 pg/ml (Table 3).

| Table 3: Univariable correlations of echocardiographic parameters with NT-proBNP ≥ 300 pg/mL. | ||||

| NT- proBNP ≥ 300 pg/ml (n = 95) | NtproBNP < 300 pg/ml ( n = 37) | OR (IC 95%) | p | |

| LVEF (%) | 54.9 ± 16.5 | 61.8 ± 7.38 | 1.04 (1.01 - 1.08) | 0.001 |

| LVH mm | 9.7 ± 1.97 | 8.97 ± 1.28 | 0.79 (0.61 - 0.99) | 0.022 |

| LA diameter | 45.8 ± 6.24 | 39.3 ± 6.69 | 0.85 (0.78 - 0.91) | <0.001 |

| S wave (cm/s) | 7.75 ± 2.91 | 9.19 ± 1.85 | 1.22 (1.06 - 1.42) | 0.001 |

| E wave (m/s) | 1.01 ± 0.26 | 0.78 ± 0.20 | 0.02 (0.00 - 0.11) | <0.001 |

| A wave (m/s) | 0.50 ± 0.49 | 0.93 ± 0.22 | 12.1 (4.19 - 43.1) | <0.001 |

| E/E’Lat | 11.6 ± 4.78 | 8.24 ± 2.34 | 0.76 (0.65, 0.87) | <0.001 |

| E/E’ Med | 15.4 ± 6.08 | 10.7 ± 2.78 | 0.78 (0.67, 0.88) | <0.001 |

| E/E’ Average | 13.5 ± 5.13 | 9.27 ± 2.41 | 0.73 (0.62, 0.84) | <0.001 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 18.0 ± 4.06 | 20.9 ± 2.88 | 1.22 (1.10 - 1.38) | <0.001 |

| RV -S wave (cm/s) | 12.3 ± 3.15 | 13.4 ± 2.36 | 1.13 (0.99 - 1.30) | 0.076 |

| IVC (mm) | 17.5 ± 4.06 | 14.7 ± 2.94 | 0.81 (0.71 - 0.91) | <0.001 |

| LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVH: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; LA: Left Atrium; TAPSE: Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion; RV: Right Ventricle; IVC: Inferior Vena Cava. | ||||

E/E’ ratio >15 was found to be significantly related to NT-proBNP ≥300pg/ml (p = 0.007), with a positive predictive value of 95%. However, two lower cut-off points (E/E’ < 15 and E/E’ <8) failed to prove useful when predicting NT-proBNP levels < 300 pg/ml (presenting false negative rates of 67% and 52%, respectively).

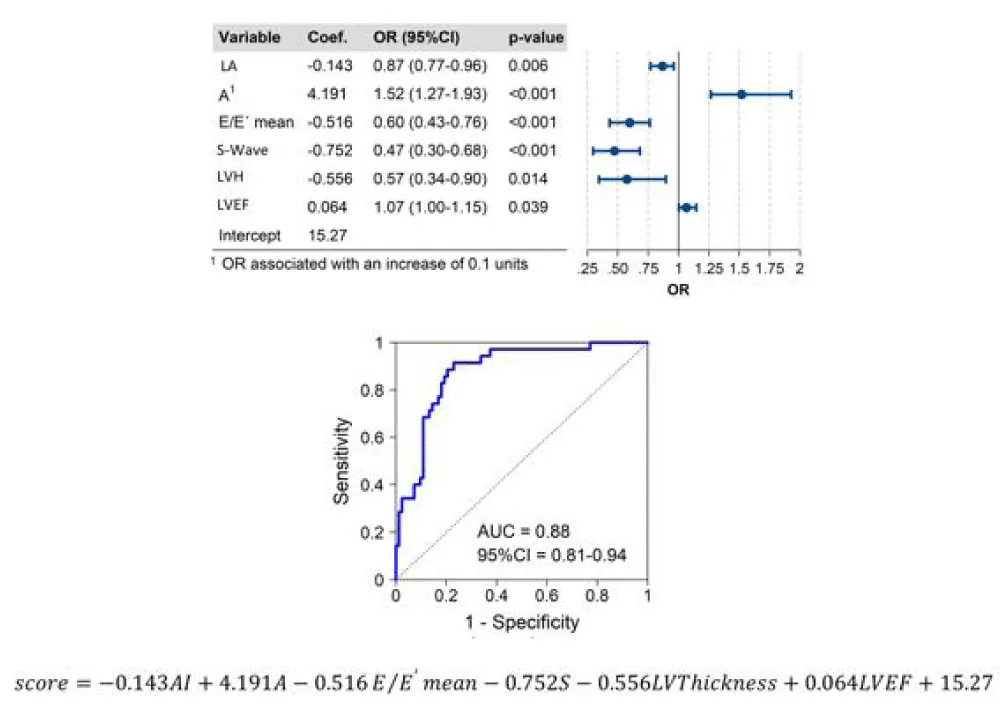

Accuracies of different predictive models for NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml are presented in Table 4. The model including only echocardiographic variables with the highest predictive power for NT-proBNP levels of ≥300 pg/ml included LA diameter, A-wave, E/E’ mean, S-wave, LV thickness, and LVEF ((AUC 0.88 (0.81 – 0.94)) (Figure 2).

| Table 4: Characteristics of different predictive models. NT-proBNP ≥ 300 pg/ml. | |||||

| Model | Variable | Coeficiente | OR | p | Area under ROC-curve (95% CI) |

| Model 1 | LVEF A1 E1 S-wave LA |

0.041 0.210 -0.236 -0.217 -0.141 |

1.042 1.234 0.790 0.805 0.869 |

0.101 0.001 0.033 0.058 0.002 |

0.81 (0.79 – 0.84) |

| Model 2 | E/E´average>15 LVEF A1 E1 S-wave LA |

-0.778 0.039 0.222 -0.183 -0.236 -0.131 |

0.459 1.040 1.248 0.833 0.790 0.877 |

0.300 0.132 0.001 0.142 0.043 0.004 |

0.81 (0.79 – 0.84) |

| Modelo 3 | LA A1 E/E´ average ≥15 S-wave LVEF ≥50 LVH |

-0.123 3.605 -4.096 -0.484 2.821 -0.502 |

0.884 1.434 0.017 0.616 16.79 0.605 |

0.008 <0.001 <0.001 0.001 0.009 0.017 |

0.86 (0.78 – 0-95) |

| Model 4 | Age LVEF A1 E1 S-wave LA |

-0.200 0.153 4.562 -4.897 -0.587 -0.201 |

0.818 1.166 1.578 0.613 0.556 0.818 |

0.002 0.001 0.001 <0.001 0.001 <0.001 |

0.93 (0.89 - 0.97) |

| Model 5 | LA A1 E/E´ average S-wave LVH LVEF |

-0.143 4.191 -0.516 -0.752 -0.556 0.064 |

0.867 1.521 0.597 0.472 0.574 1.066 |

0.006 <0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.014 0.039 |

0.88 (0.81 - 0.94) |

| LVEF: Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; LVH: Left Ventricular Hypertrophy; LA: Left Atrium. | |||||

Figure 2: Central illustration. ROC analysis revealed the reliability of the final model using age and echocardiographic parameters to predict NtproBNP≥300 pg/ml. ROC receiver operating characteristic; LA, left atrium, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH left ventricular thickness.

To avoid the heterogeneity and subjectivity of previous definitions of heart failure, the universal definition of heart failure requires not only the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms caused by structural or functional cardiac abnormalities but also objective evidence of cardiogenic systemic or pulmonary congestion [2]. While natriuretic peptide levels supporting the definition of heart failure have been defined both for ambulatory and hospitalized or decompensated patients, the values of echocardiographic parameters indicating elevated filling pressures have not yet been established for all types of heart failure [3]. Echocardiographic variables have been defined for some phenotypic variants of heart failure such as heart failure with preserved LVEF [8], but consensus has not been reached as to parameters corresponding to definition of heart failure [2,3]. In previous studies, E/E’ has demonstrated correlation with elevated pulmonary capillary pressure [4-6]. However, it has not been accepted as an indicator of congestion [2,3].

Our study is the first to present a predictive model for values of NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml (levels supporting the diagnosis of heart failure for hospitalized or decompensated patients) using clinical variables and echocardiographic parameters in the context of the universal definition of heart failure. Variables included in the model included NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml included LA diameter, A-wave, E/E’ mean, S-wave, LV thickness, and LVEF.

Our univariate analysis demonstrated that an elevated Doppler E/E’ ratio was associated with NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml, but this association was not confirmed upon multivariate analysis. In our univariate analysis, we analyzed E/E’ as a continuous variable. When we divided our sample into two groups, those with E/E’ > 15 and those with E/E’ ≤ 15, we found that an E/E’ ratio > 15 presented a high positive predictive value for NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml. It is probable that this ratio is highly useful in clinical practice to predict heart failure due to its easily obtainable nature and its high positive predictive value. Two lower cut-off points (E/E’ < 15 and E/E’ < 8) failed to prove useful when predicting NT-proBNP levels < 300 pg/ml, probably related to the delay in the decrease in NT-proBNP levels after diuretic treatment.

In our study, elevated E-wave values are predictive of NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml. This finding is in line with other studies which demonstrate that elevated E wave values are associated with left ventricle filling velocities and as such, with higher left atrial pressures and pulmonary capillary pressure [4-6]. The left atrial diameter, which demonstrated statistical significance upon multivariant analysis, is associated with maintained high pressures. LVEF and S-wave values, which were found to have an inversely proportional relationship with NT-proBNP levels, are both used in clinical practice to assess systolic function, and inferior values suggest the possibility of heart failure.

Our results also demonstrate that including age as a variable can increase predictive power, as demonstrated in Model 4. However, as NT-proBNP increases physiologically with age, we decided to exclude it from the final model presented in this study.

Since its introduction in the early 1950s, echocardiography has quickly become a pillar of cardiovascular medicine, with multiple advantages including its non-invasive nature, safety, accessibility, and instantly available results. In recent years, point-of-care echocardiography has become more frequent, expanding the accessibility of the technique to areas such as emergency medicine and primary care [9-11]. Natriuretic peptide levels, while easily available in most tertiary hospitals, are not always immediately available in smaller centers, emergency departments, primary care, and outpatient facilities, pointing to the utility of establishing a correlation between values of natriuretic peptides indicative of heart failure and echocardiographic parameters [12,13].

This study presents several limitations. Firstly, our reference level of NT-proBNP, although proposed by clinical guidelines and consensus documents to define heart failure in hospitalized or decompensated patients, has been shown to have a high negative predictive value, but studies differ as to its positive predictive value. However, this has not deterred experts from including these levels as diagnostic criteria for heart failure [2,3].

Although a formal inter-observer variability analysis was not systematically performed, measurements were obtained using standardized acquisition and analysis protocols, which have been shown to ensure good reproducibility in previous studies [14]. All echocardiographic measurements were performed by experienced operators following current guideline recommendations. Patients with atrial fibrillation were excluded from the present study because of the well-known beat-to-beat variability associated with this arrhythmia, which may significantly affect the accuracy and reproducibility of several echocardiographic parameters. Consequently, the results of this study should be primarily interpreted in patients in sinus rhythm, and further studies including patients with atrial fibrillation are warranted to determine whether these findings can be extrapolated to this population. Previous data have shown that atrial fibrillation is associated with higher NT-proBNP concentrations even in the absence of overt heart failure [8]. Excluding patients with atrial fibrillation therefore allowed us to minimize potential confounding related to these pathophysiological alterations and to better isolate the relationships under investigation. Nevertheless, this exclusion may limit the generalizability of our findings, as atrial fibrillation is highly prevalent in patients with occult heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, independent of other clinical variables [15].

Finally, our predictive model is subject to the conditions of our study population, and multicenter studies are needed to confirm its generalizability.

This article reports the correlation between clinical and echocardiographic parameters and elevated NT-proBNP levels and presents an accurate predictive model for NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml, a diagnostic criterion for heart failure in hospitalized and decompensated patients. Factors shown to be highly predictive of NT-proBNP ≥300 pg/ml included age, E-wave, A-wave, S-wave, LVEF, and the left atrial diameter. Our research serves to define echocardiographic parameters suggestive of cardiogenic pulmonary or systemic congestion, which can apply to the complete phenotypical spectrum of heart failure.

Acknowledgment: Dra Pfang de la UICO editorial (Quirónsalud Red 4H).

- Romano M. Heart failure syndromes: different definitions of different diseases—do we need separate guidelines? A narrative review. J Clin Med. 2025;14(14):5090. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/14/14/5090

- Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23(3):352-380. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejhf.2115

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):4-131. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/42/36/3599/6358045

- Appleton CP, Galloway JM, Gonzalez MS, Gaballa M, Basnight MA. Estimation of left ventricular filling pressures using two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography in adult patients with cardiac disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(7):1972-1982. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/0735-1097(93)90787-2

- Nagueh SF, Middleton KJ, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Quiñones MA. Doppler tissue imaging: a noninvasive technique for evaluation of left ventricular relaxation and estimation of filling pressures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30(6):1527-1533. Available from: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00344-6

- Ommen SR, Nishimura RA, Appleton CP, Miller FA, Oh JK, Redfield MM, et al. Clinical utility of Doppler echocardiography and tissue Doppler imaging in the estimation of left ventricular filling pressures. Circulation. 2000;102(15):1788-1794. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/01.CIR.102.15.1788

- McDonagh TA, Holmer S, Raymond I, Luchner A, Hildebrant P, Dargie HJ. NT-proBNP and the diagnosis of heart failure: a pooled analysis of three European epidemiological studies. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(3):269-273. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1388984204000154

- Formiga F, Nuñez J, Castillo Moraga MJ, Cobo Marcos M, Egocheaga MI, et al. Diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic narrative review of the evidence. Heart Fail Rev. 2024;29:179-189. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10741-023-10360-z

- Johri AM, Glass C, Hill B, Jensen T, Puentes W, Olusanya O, et al. The evolution of cardiovascular ultrasound: a review of cardiac point-of-care ultrasound across specialties. Am J Med. 2023;136(7):621-628. Available from: https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(23)00108-4/fulltext

- Allimant P, Guillo L, Fierling T, Rabiaza A, Cibois-Honnorat I. Point-of-care ultrasound to assess left ventricular ejection fraction in heart failure in unselected patients in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2025;42. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/fampra/article/42/2/cmae040/7607821

- Grenar P, Jakl M, Mědílek K, Nový J, Kočí J, Vaněk J, et al. Effect of point-of-care echocardiography by noncardiologists on patient management in acute chest pain. Intern Emerg Med. 2025. Epub ahead of print. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11739-025-04198-6

- Bayes-Genis A, Rosano G. Unlocking the potential of natriuretic peptide testing in primary care: a roadmap for early heart failure diagnosis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25(8):1181-1184. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ejhf.2950

- Taylor CJ, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Lay-Flurrie SL, Goyder CR, Taylor KS, Jones NR, et al. Natriuretic peptide testing and heart failure diagnosis in primary care: diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Gen Pract. 2022;73(726). Available from: https://bjgp.org/content/73/726/e61

- Taub CC, Stainback R, Abraham T, Sengupta PP, Sorrell VL, Strom FJ, et al. Guidelines for the standardization of adult echocardiography reporting. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2025;38(7):735-774. Available from: https://www.onlinejase.com/article/S0894-7317(25)00292-5/fulltext

- Reddy YNV, Obokata M, Gersh BJ, Borlaug BA. High prevalence of occult heart failure with preserved ejection fraction among patients with atrial fibrillation and dyspnea. Circulation. 2018;137(5):534-535. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030093